Radiative forcing

In climate science, radiative forcing is generally defined as the change in net irradiance between different layers of the atmosphere. Typically, radiative forcing is quantified at the tropopause in units of watts per square meter. A positive forcing (more incoming energy) tends to warm the system, while a negative forcing (more outgoing energy) tends to cool it. Sources of radiative forcing include changes in insolation (incident solar radiation) and in concentrations of radiatively active gases and aerosols.

Contents |

Radiation balance

The vast majority of the energy which affects Earth's weather comes from the Sun. The planet and its atmosphere absorb and reflect some of the energy, while long-wave energy is radiated back into space. The balance between absorbed and radiated energy determines the average temperature. The planet is warmer than it would be in the absence of the atmosphere: see greenhouse effect.

The radiation balance can be altered by factors such as intensity of solar energy, reflection by clouds or gases, absorption by various gases or surfaces, emission of heat by various materials, and other factors related to climate change. Any such alteration is a radiative forcing, and causes a new balance to be reached. In the real world this happens continuously as sunlight hits the surface, clouds and aerosols form, the concentrations of atmospheric gases vary, and seasons alter the ground cover.

IPCC usage

The term “radiative forcing” has been used in the IPCC Assessments with a specific technical meaning, to denote an externally imposed perturbation in the radiative energy budget of Earth’s climate system, which may lead to changes in climate parameters.[1] The exact definition used is:

- The radiative forcing of the surface-troposphere system due to the perturbation in or the introduction of an agent (say, a change in greenhouse gas concentrations) is the change in net (down minus up) irradiance (solar plus long-wave; in Wm-2) at the tropopause AFTER allowing for stratospheric temperatures to readjust to radiative equilibrium, but with surface and tropospheric temperatures and state held fixed at the unperturbed values.[2]

In a subsequent report,[3] the IPCC defines it as:

"Radiative forcing is a measure of the influence a factor has in altering the balance of incoming and outgoing energy in the Earth-atmosphere system and is an index of the importance of the factor as a potential climate change mechanism. In this report radiative forcing values are for changes relative to preindustrial conditions defined at 1750 and are expressed in watts per square meter (W/m2)."

In simple terms, radiative forcing is "...the rate of energy change per unit area of the globe as measured at the top of the atmosphere."[4] In the context of climate change, the term "forcing" is restricted to changes in the radiation balance of the surface-troposphere system imposed by external factors, with no changes in stratospheric dynamics, no surface and tropospheric feedbacks in operation (i.e., no secondary effects induced because of changes in tropospheric motions or its thermodynamic state), and no dynamically induced changes in the amount and distribution of atmospheric water (vapour, liquid, and solid forms).

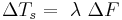

Radiative forcing can be used to estimate a subsequent change in equilibrium surface temperature (ΔTs) arising from that radiative forcing via the equation:

where λ is the climate sensitivity, usually with units in K/(W/m2), and ΔF is the radiative forcing.[5] A typical value of λ is 0.8 K/(W/m2), which gives a warming of 3K for doubling of CO2.

Example calculations

Radiative forcing (often measured in watts per square meter) can be estimated in different ways for different components. For the case of a change in solar irradiance, the radiative forcing is the change in the solar constant divided by 4 and multiplied by 0.7 to take into account the geometry of the sphere and the amount of reflected sunlight. For a greenhouse gas, such as carbon dioxide, radiative transfer codes that examine each spectral line for atmospheric conditions can be used to calculate the change ΔF as a function of changing concentration. These calculations can often be simplified into an algebraic formulation that is specific to that gas.

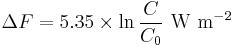

For instance, the simplified first-order approximation expression for carbon dioxide is:

where C is the CO2 concentration in parts per million by volume and C0 is the reference concentration.[6] The relationship between carbon dioxide and radiative forcing is logarithmic so that increased concentrations have a progressively smaller warming effect.

Formulas for other greenhouse gases such as methane, N2O or CFCs are given in the IPCC reports.[7]

Related measures

Radiative forcing is intended as a useful way to compare different causes of perturbations in a climate system. Other possible tools can be constructed for the same purpose: for example Shine et al.[8] say "...recent experiments indicate that for changes in absorbing aerosols and ozone, the predictive ability of radiative forcing is much worse... we propose an alternative, the 'adjusted troposphere and stratosphere forcing'. We present GCM calculations showing that it is a significantly more reliable predictor of this GCM's surface temperature change than radiative forcing. It is a candidate to supplement radiative forcing as a metric for comparing different mechanisms...". In this quote, GCM stands for "global circulation model", and the word "predictive" does not refer to the ability of GCMs to forecast climate change. Instead, it refers to the ability of the alternative tool proposed by the authors to help explain the system response.

See also

References

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/212.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/214.htm#611

- ^ http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/syr/ar4_syr.pdf

- ^ Rockstrom, Johan; Steffen, Will; Noone, Kevin; Persson, Asa; Chapin, F. Stuart; Lambin, Eric F.; et al., TM; Scheffer, M et al. (2009). "A safe operating space for humanity". Nature 461 (7263): 472–475. doi:10.1038/461472a. PMID 19779433.

- ^ http://www.grida.no/publications/other/ipcc_tar/?src=/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/222.htm

- ^ Myhre et al., New estimates of radiative forcing due to well mixed greenhouse gases, Geophysical Research Letters, Vol 25, No. 14, pp 2715–2718, 1998

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/222.htm

- ^ Shine et al., An alternative to radiative forcing for estimating the relative importance of climate change mechanisms, Geophysical Research Letters, Vol 30, No. 20, 2047, doi:10.1029/2003GL018141, 2003

- IPCC glossary http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/glossary/ar4-wg1.pdf

External links

- CO2: The Thermostat that Controls Earth's Temperature by NASA, Goddard Institute for Space Studies, October, 2010, Forcing vs. Feedbacks

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fourth Assessment Report (2007), Chapter 2, “Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and Radiative Forcing,” pp. 133–134 (PDF, 8.6 MB, 106 pp.).

- NOAA/ESRL Global Monitoring Division (no date), The NOAA Annual Greenhouse Gas Index. Calculations of the radiative forcing of greenhouse gases.

- U.S. EPA (2009), Climate Change – Science. Explanation of climate change topics including radiative forcing.

- United States National Research Council (2005), Radiative Forcing of Climate Change: Expanding the Concept and Addressing Uncertainties, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate

- A layman's guide to radiative forcing, CO2e, global warming potential etc